The big reveal

May 25, 2011

How would you feel if genome analysis revealed you were predisposed to “early sudden death” from vascular disease? Less hungry for chips? Determined to blow all your savings in Vegas and have as much sex as the day is long? And what if a message in your inbox from a lab in sunny California coldly stated that you had a 98.2 % chance of developing Alzheimer’s since, yup, there it is, you’ve got the “E4 variant” of the APOE gene? Would you be grateful for the knowledge — isn’t all knowledge power in the Information Age? — or annihilated by existential dread, and asking, Now what?

No, I better not. Well, maybe just one. Och.

No, I better not. Well, maybe just one. Och.

If you’re like me, adopted and clueless about the diseases in my family tree, wary of palm readers glaring at my lifeline and the daughter of an adoptive mother in the final stages of Alzheimer’s and a dad dead and gone from heart failure, the arrival of consumer genomics is both unnerving and intriguing. In my case, genetic testing could potentially fill in some blanks in my life story I can’t get the old-fashioned way: by observing family members, then watching my body gradually sink into my mother’s genes.

A three-year search for my birth mother by the Children’s Aid Society yielded zero information about my medical history and only a sprinkling of anecdotes about my birth parents. She was 5’6” with brown hair, blue eyes and a “lively face. She loved to draw and was an “avid reader.” In fact, she went to art school in London, England during the city’s finest hour, the mid-sixties (read: the Stones, the Beatles, Mary Quant minis, velvet suits and jumbled teeth). She met my biological father during a stint in Canada as a nanny. Records describe him as “very tall and striking” and from “a prominent family.” So I was a scandal. She was 19 and he was 20 when my budding existence became undeniable.

She met my biological father during a stint in Canada as a nanny. Records describe him as “very tall and striking” and from “a prominent family.” So I was a scandal. She was 19 and he was 20 when my budding existence became undeniable.

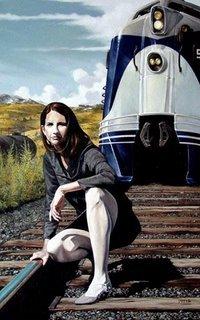

I found this out in 2004. Back then the provincial government in Ontario was still keeping a lock on adoption records. But since the summer of 2009 adoption records have been opened and adoptees are now free to find out more information about their medical history and the names on their birth certificates. Actually, I already know my original name: it’s Tagart.  “Hmm, like Dagny Taggart in The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged,” said my friend, Ian, an Ayn Rand fanatic. I’m put off by objectivism and haven’t read Rand’s novels, but according to Ian, Ms. Taggart is a beautiful and powerful railway executive who’ll stop at nothing to get what she wants. I feel sweeter than that.

“Hmm, like Dagny Taggart in The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged,” said my friend, Ian, an Ayn Rand fanatic. I’m put off by objectivism and haven’t read Rand’s novels, but according to Ian, Ms. Taggart is a beautiful and powerful railway executive who’ll stop at nothing to get what she wants. I feel sweeter than that.

In the meantime, I’ve applied to learn more about my medical history, but getting an answer could take months, even years. And, in the end, I may be no further ahead if my biological parents decide to exercise their right to disclosure vetoes.

Having my DNA sequenced, by comparison, could take 6-8 weeks, yielding genomic data that, among other things, could tell me if I carry inheritable markers for over 20 diseases, like breast cancer and Alzheimer’s, and whether I’m at risk for almost 80 different disorders, such as type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s and brain aneurysms. It could also predict how I’d react to certain medications, including hormone replacement therapy, which is temping as the decades mount. So should I do it?

The spit test from 23andMe.com

The spit test from 23andMe.com

An editor started me on this journey last year when she called to ask if I’d take on a story about Do-It-Yourself genome sequencing kits. “I want you to go out and find out how the test results from these kits are customizing care,” she said. “How are they changing the face of healthcare by individualizing our treatment options?”

Whether she knew it or not, my editor was echoing Bill Clinton’s Rose Garden speech in the summer of 2000, made not long after scientists wrapped up the Human Genome Project. Back then the president stood at the lectern and predicted:

Human kind is on the verge of gaining immense, new power to heal. Genomics will revolutionize the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of most, if not all human diseases.

And it probably will, but just not now. My story fizzled.

Here’s the deal (and what I told my editor after combing the landscape for hopeful advances). Genome sequencing hasn’t changed primary health care, yet. Experts are unanimous in saying its current impact is very limited. We’re still on the verge of that revolution. Like the dot.com boom a decade ago, it’s another example of us putting too much faith in untested ideas and expecting instant payoff from our technological brilliance.

A good example of that happened last May. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had to acknowledge that the genetic revolution had roared ahead of the health care realities when it abruptly blocked the selling personal genetics testing kits at Walgreens drugstores, just 48 hours before they were due to hit the shelves. The official reason: the boxes were missing an FDA clearance and approval number. The National Society of Genetic Counselors then stepped forward next to identify the real concern: “[R]eceiving genetic information directly from a manufacturer or supplier without input from a qualified health care provider increases the chance for misunderstanding or misinterpretation of results,” they said in an official statement. Also, people need to be “prepar[ed] for what they might learn,” added NSGC president Elizabeth Kearney in the same statement. So we’re back to being on the verge of a genetic revolution.

What we do know for sure is that having the gene for Huntington’s Disease is the only example where, if you’ve got the gene, you’ll get the disease. 100% without a doubt. Genetic testing can also predict if you’re a carrier for cystic fibrosis and Tay Sachs. But we’ve known that and have been testing for those diseases for over 30 years. When it comes to cancer, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and heart disease, there’s no telling if you’ll get any one of these deadly disorders even if the markers on your genes light up like a Christmas tree. Genome sequencing is not a diagnostic tool or, as Steven Pinker says, it’s not like taking a pregnancy test that tells you yes or no if you’re carrying a child.

What’s better ten years after Clinton’s speech are the tools. The genome-sequencing rate is faster; what used to take years can be done in a day. And just as significant is the drop in the price of sequencing, from millions to thousands to just a couple of hundred bucks in a few short years. In a recession, though, it’s a hard sell, especially in the US where these testing companies are based.

When the experts say genomics is having a “limited” impact on medicine, this is what they mean:

• even though the full genome has been sequenced, at this point only 1.5% of all human genes code for the proteins that make up our cells and tissues. Scientists haven’t identified what the rest are doing. As science writer, Brandon Keim, put it in a Wired feature in the spring of 2010 “Even after the publication of hundreds of genome-wide association studies — the gold standard of disease gene hunting, in which thousands of genomes are scanned and compared — scientists can explain only a fraction of the heritability that clearly exists in common diseases and conditions. … But they hope ongoing projects will fill massive gaps that remain in current genetic explanations for most common diseases.”

[pullquote]Huge amounts of data will lead to predictions based on patterns. Only then can therapeutic applications be developed.[/pullquote]

• Last summer, Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD and director of the National Human Genome Research Institute from 1993-2008, gave an update on genomics in Nature magazine’s April issue. He said “Primary care providers aren’t even close to practicing genetic medicine.” He added, “The most profound consequence of the genetic revolution in the long run will be the development of targeted therapeutics based on a detailed molecular understanding of pathogenesis.” But, again, it hasn’t happened.

Still, reporters continue to buzz around genomics.

Journalists love revolutions, be they in Egypt or in a test tube. Check out Joseph Hall’s “I am Joe’s DNA” in last weekend’s Sunday Star. So far the majority of volunteers who have sent off their spit to be sequenced are Nobel laureates, clinical researchers and journalists. The general public still isn’t interested, even though the price for the kits runs as little as $300 USD through internet-based companies like 23andMe. This Mountain View, California-based biotech company was started by Anne Wojciki, a biologist, biotech analyst and wife of Google co-founder, Sergey Brin. Google is heavily invested in the company. Brin is looking to genomics for a cure for Parkinson’s. His mother has the disease and so may he one day.

23and Me wants to “empower individuals to take bold and informed steps toward self knowledge” and “accelerate research” through the combined potential of the internet and genetics. Once you receive your genetic report card, 23andMe “keeps you up-to-date with the latest biomedical literature so you can understand firsthand how breaking scientific news relates directly to you.”

But the low turnout from the average North American suggests the Genomics Age and the general public haven’t found one another yet — despite efforts to make sequencing understandable, even sexy (23andMe even threw swishy “spit parties”). As of last spring 23andMe has laid off almost half its staff (from 70 to 40). It is also now declining media interviews as it ponders its future. In 2010 Navigenics, another genetic testing company, went through 3 executive officers in a year and deCODE Genetics just “passed through bankruptcy.” All three testing companies are now more focused on selling to doctors, not consumers, says The New York Times.

In 2011, we are in the collecting and analyzing phase of the impending revolution. More data is needed, so more people need to sign on for a spit test. One thing is clear: affordable genetic testing kits are a great example of the crowd sourcing trend started by Wikipedia and Google Analytics — only the data is human DNA. It’s medicine 2.0, as it were. Huge amounts of data will lead to predictions based on patterns. Only then can therapeutic applications be developed.

[pullquote]Genetic testing kits are a great example of the crowd sourcing trend started by Wikipedia and Google Analytics.[/pullquote]

So where does this leave me? No further ahead, really, than when I first started researching genomics and my biological origins.

Right then, back to life.

Leave a Reply