Spotlight: Vanishing accents

April 15, 2012

I’ve been covering music, and especially music and the internet, a fair bit lately. Here’s a piece I published last year that tackles the mystery of singing and accents. Enjoy!

SPOTLIGHT is Society Pages’ newest column focusing on questionable occurrences

In 1981, Sheena Easton was a 22-year old club kid with a glossy pout and a Lady Di shag when she burst onto the American music scene with a finger-snapping tune called “Morning Train.” The song went all the way to Number One on Billboard Magazine‘s adult contemporary chart. But when Easton sat down for her first interview with Entertainment Tonight, the production control room had to post subtitles across her bare shoulders to translate the singer’s accent — a Glaswegian cant so thick it strained Mary Hart’s smile and made TV viewers adjust the antennae on their sets.

In 1981, Sheena Easton was a 22-year old club kid with a glossy pout and a Lady Di shag when she burst onto the American music scene with a finger-snapping tune called “Morning Train.” The song went all the way to Number One on Billboard Magazine‘s adult contemporary chart. But when Easton sat down for her first interview with Entertainment Tonight, the production control room had to post subtitles across her bare shoulders to translate the singer’s accent — a Glaswegian cant so thick it strained Mary Hart’s smile and made TV viewers adjust the antennae on their sets.

The disconnect between Easton’s clear and powerful singing voice and her conversational brogue may have come as a surprise to the viewing public, but it makes perfect sense to voice experts who cite Easton, Liverpool’s Fab Four (that’s right, The Beatles), Sweden’s Ace of Base and Céline Dion, the chanteuse of Charlemagne, Québec, as good examples of strong regional accents that have been neutralized (or Americanized) by song. Diction lessons, mimicry and whip-snapping managers with US dollar signs in their eyes only partially explain this vocal transformation. That’s when I started digging for an answer.

“I’ve heard Chinese school kids with minimal English language skills sing songs in English with almost perfect American accents,” Randy Wong, a Boston-based professional musician and educator, told me in an email when I recounted the Easton story. And that’s because when children sing they rarely act self conscious about forming this mouths into big O’s, says Dr. Brian Hands, weighing in on this mystery. Hands is a Toronto-based laryngologist and voice care specialist who tends to the voices of COC opera singers, Stratford actors and visiting rocks stars. “You can mask any accent with a large articulator and resonator,” he says.

My reinterpretation of a greeting card, since lost.

My reinterpretation of a greeting card, since lost.

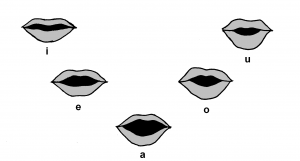

Here’s what he means: go on YouTube and watch your favourite singer — pop or classical — and you’ll find, says Hands, that “the best ones open their mouths like they’re going to swallow the stage.” They inhale using their diaphragm and when they exhale into song they promptly drop their tongue, their jaw (the articulator) and their voice box (the resonator), creating as wide a chamber as possible. “Such a large space means they can lengthen the time they hold their vowels, and it’s the vowels that are responsible for carrying the melody and the sound.”

Take Céline Dion. In person, she’s a fast talker with a pronounced nasality (Quebecois vowels are closed and nasal, wah, wah, wah).

Here’s a sample if you need a refresher (“Céline” appears at the 2:30 mark of this spoof about Canadian accents and -isms:

When Céline belts out one of her anthems — oh, like, “My Heart Will Go On” — she changes the shape of her vocal tract and stops letting air escape through her nose. “All that extra space and breath goes into managing an open-toned singing voice,” says Lorna MacDonald, a fiery soprano who is a colleague and patient of Doc Hands. “The expanded vowel space in her mouth leads to changes in pronunciation and a greater warmth and back-roundedness more typical of English speech patterns,” she explains. In other words, that process of stretching, rounding out and amplifying the vowels is what anglicizes most regional accents.

When she’s not on stage or in the studio making recordings for the CBC, MacDonald heads up the voice pedagogy program in the music department at The University of Toronto. I met with her at her office which is packed with books, music scores and anatomical models of human heads and chest cavities with brightly-coloured voice boxes caught in the throats.

But there’s one more consideration: accents are also about timing. At least, that’s what Marla Roth, a Toronto speech pathologist told me. “The same thing happens with people who stutter. We’ve found that when they sing, they don’t stall and trip over their words as much.” Everything in normal speech is about timing; you have to hit the right points in your mouth at the right moment. “In singing,” says Roth, the timing and intonation are off from normal speech, and that can result in a new speech characteristic.”

That leaves us, then, with only one mystery to solve. Mick Jagger. How is it that the biggest mouth in rock and roll turned an East London accent into a stuttering southern drawl?

P.S. Steven Tyler, another big mouth, doesn’t work in this story. Despite being from Yonkers he has a standard American accent with a slight tinge of surfer dude, so not much to overcome.

Leave a Reply