Warp speed

September 24, 2014

My favourite moments in Star Trek, the original series, weren’t the fight scenes where scrums of Beatle-booted characters threw fake punches and ricocheted off walls with a little too much actorly enthusiasm. And it wasn’t when Spock grew a beard and waxed poetic about the universe. And it certainly wasn’t when Kirk fell in love. I got embarrassed every time the lens misted up and the Stratford-trained captain pursued his next interplanetary go-go dancer. No, I liked it best when we looked past the back of Captain Sulu’s head, through the modest windshield of the Starship Enterprise, and experienced the onslaught of an oncoming asteroid field.

“Bring us through, Mr Sulu! / Star Trek fan blender space animation” by Pirogronianus. Creative Commons Attribution Licence: Reuse Only.

I’d say that those Star Trek sequences, plus the opening credits where the ship zooms away at warp speed, were my first experience moving through infinity. Even on a crummy black and white Zenith TV those simulated navigation scenes gave me a mini head rush. Not bad for 1966 special effects! It wasn’t until 1977, and the premiere of Star Wars on the big screen, that I experienced an even stronger white knuckle adrenaline rush through the windshield of the Millennium Falcon, with a young Harrison Ford at the controls.

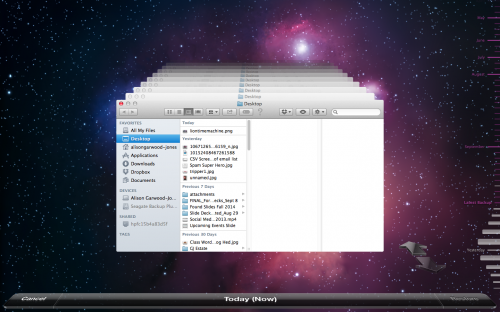

These days my screen has shrunk back down to 15 inches, but the feeling of infinity I get looking out on cyber space is part joy ride/part mournful bargain. Here’s what’s fun: my cockpit has an external drive hooked up to Time Machine, a backup mechanism that unfolds like a sci-fi episode I like to call, Found In Space!

Moving your cursor over the Time Machine screen takes you through an accordion file of past desktops (above). There they are, floating in zero gravity against a gassy, star-studded universe. I get my “star fix” from that.

But even with my knowledge of space travel limited to the imaginative outpourings of Gene Roddenberry, George Lucas and the engineers at Apple, I’ve come to a few conclusions about navigating cyber space vs. the cinematic presentation of space:

• In cyber space, the endless expansion of ideas and junk, year over year, feels like a smaller version of the Big Bang that created the universe. The latter posits that a galactic “explosion” took all matter from one place then flung it outwards in every direction, never to stop moving. But here’s the thing: watching fake asteroids whoosh by on a movie screen is way more fun than the head rush/ache I get watching books explode and words and letters zoom past at warp speed across my screen.

• The idea that pixels unsteady us, visually, is accepted as fact. Web developers, like John McWade, will tell you that this elusive physical sensation is due, largely, to the fact of there being no reliable print to web pixel per inch (ppi) conversion. When you take something from print to digital, says McWade, you need to take into consideration multiple ppi’s, screen responses and even screen colour temperatures. All too often, developers never get it right, especially when they are trying to configure the same thing across desktop, tablet and mobile screens. These limitations are making our heads and eyes swirl. But I also think our emotions are getting sucked into the optical black hole .

• We still need to understand the psychological effect of shaky visuals and bottomless speed reading that’s loaded down with multiple side routes to social media. The only way to steady ourselves may be to reintroduce a healthy balance of paper back into our lives at the same time we continue to delve deeper into technology. When we do, books will become intellectual havens and sandboxes instead of medieval word delivery systems. This argument runs parallel to those calling for a reintroduction of solitude and absence in our lives. “You can’t think of a new or game-changing thought if you’re living in an echo chamber,” Michael Harris, author of the book The End of Absence, told Nora Young in a recent episode of Spark. “You have to remove yourself and carve room for absence.”

So, despite the endless possibilities available to me from my keyboard, including the entire Library of Congress (I haven’t touched it, have you?), I keep coming back to the emotional significance of words designed to be at one with a surface they’re on. Words are the not only thing at one with the page, so am I. What’s more, pages corralled between two covers don’t fence in my imagination, they offer a platform on which to leverage my imagination even further afield.

This is only a guess, but I’m thinking that when our eyes and brain detect the physicality of ink on paper, it sends a different message to our brain’s emotional core, one that tells us we are standing on solid ground. That physicality, combined with the absence of social media sharing buttons, sets me up to relax, absorb and really think. There must be studies published that say this. Maybe I’ve read them? I just haven’t found them in time for this blog post. Please share if you know of any.

Finally, I love the feeling of being at one with a writer. I’ve had it reading Alice Munro, Daniel Boorstin, Billy Collins, Robert Fulford and many others. I’m a better person because of that. But this breathless rush of digital culture is shrinking my sense of self, as far as I can tell. It’s certainly shrunk my memory muscle. I’m re-engineering my life to fix that. It starts with holding a book.

Captain Kirk left these behind.

Leave a Reply