In Conversation with Anita Kunz

May 19, 2016

hen Anita Kunz was a five-year old growing up in Kitchener, Ontario in the early 1960s, she practiced drawing the usual kid stuff: horses, flowers, fluffy clouds. But making Crayola masterpieces for the fridge wasn’t enough. Anita drew with a stronger sense of purpose learned from her uncle, the artist and environmentalist Robert Kunz. His editorial illustrations for the “The Children’s Corner,” a weekly full-page section in the Toronto Telegram, introduced youngsters like Anita to a range of current affairs and delightfully drawn explanations of the world around them (things like, “where honey comes from”). “Uncle Robert taught me that an artist’s work could actually play a meaningful role in society and in culture, whether as education or journalism,” says Kunz. “That focus in me came very early on.”

hen Anita Kunz was a five-year old growing up in Kitchener, Ontario in the early 1960s, she practiced drawing the usual kid stuff: horses, flowers, fluffy clouds. But making Crayola masterpieces for the fridge wasn’t enough. Anita drew with a stronger sense of purpose learned from her uncle, the artist and environmentalist Robert Kunz. His editorial illustrations for the “The Children’s Corner,” a weekly full-page section in the Toronto Telegram, introduced youngsters like Anita to a range of current affairs and delightfully drawn explanations of the world around them (things like, “where honey comes from”). “Uncle Robert taught me that an artist’s work could actually play a meaningful role in society and in culture, whether as education or journalism,” says Kunz. “That focus in me came very early on.”

Anita Kunz’s uncle, artist Robert Kunz.

Anita Kunz’s uncle, artist Robert Kunz.

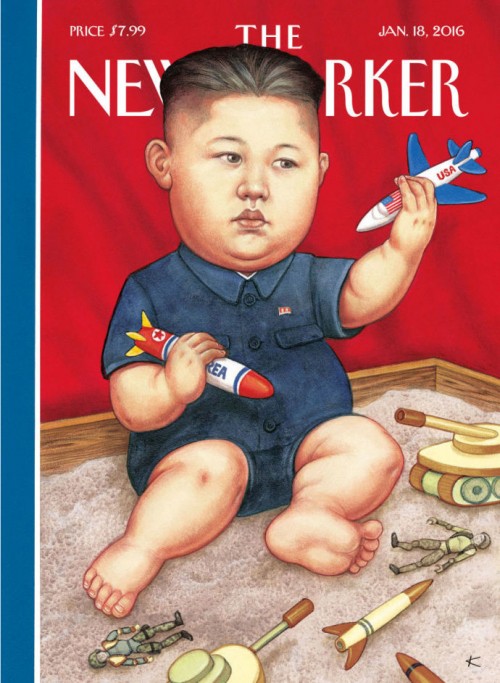

But whereas Robert Kunz’s cast of characters were dwarves and chatty forest creatures, like Mayor Rob Rabbit of Acorn Valley, his niece would eventually take on real political animals whose strange habits and questionable tactics were recast in her hard-won signature style: an off-kilter hyperrealism with elements of fantasy and surrealism. A naked and exposed portrait of President Bill Clinton for a 1998 cover of the now-defunct Saturday Night magazine is typical of Kunz giving her point of view as a feminist and democratic citizen. The same goes for her recent depiction of Kim Jong-un, supreme leader of North Korea, whom Kunz depicts as a big baby playing in his sandbox with some new toy nuclear missiles. “I have to admit,” says Kunz, “with that cover I had a few moments where I thought, ‘Oh, shit, are there going to be repercussions on the Internet?’” Like most of her illustrations, the idea was self-generated and pitched to The New Yorker, who put it on a cover this past January.

“New Toys,” North Korea’s Kim Jong-un for The New Yorker, Jan 18. 2016. “As an artist, this whole idea that we can be so incredibly smart and technologically-savvy—with space travel, mapping the genome, etc.—and then be such idiots, at the same time. I can’t believe there’s this paradox! Talk about inspiration for an illustrator’s work,” Kunz says. She installed a wall-mounted TV opposite her drawing board and has CNN streaming while she works. Knowing what’s happening in the world and with different cultures is central to her concept-driven art.

To students and competitors, Kunz is known for having scaled every mountain in publishing, multiple times, with her covers and editorial drawings for Time magazine, Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, Atlantic Monthly, Toronto Life and The New York Times (the paper and magazine). For the first five years of her career, however, this OCAD grad (class of ’78, when it was still OCA) fielded one rejection letter after another. “I wish I’d kept them all,” she says. “People told me I wasn’t in the same league as some of the male artists.” Somehow, she blotted out the sexist insults and got back to work filling her “box of ideas” with funny and mournful sketched observations of human nature, while feeding off the socially and politically charged works of illustrators she admired, like Sue Coe, Brad Holland and Marshall Arisman.

[pullquote]Golden AACE Image winner Anita Kunz looks back on her 35-year career and how she developed a knack for sharp editorial commentary[/pullquote]

Given the widespread pressure to brand ourselves, Kunz likes to remind the curious and ambitious that she didn’t spring from the classrooms of OCAD fully formed (remember those rejections). “Everyone talks about a style and I know students just graduating especially feel pressure to settle on one, but my style evolved naturally.” It developed the way it did largely because she didn’t rely too heavily on references. “I drew from my head and that’s why my work has always seemed a bit wonky.” And she drew constantly. “The more you practice, the more you’ll get a look that’s uniquely yours.”

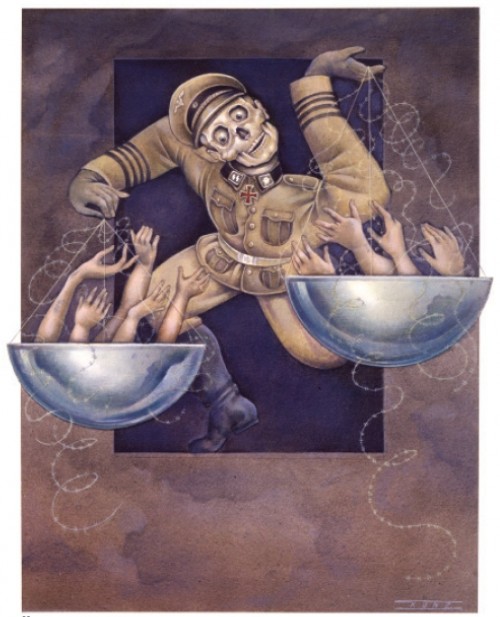

Her first significant assignment came in 1982 when Saturday Night art director Louis Fishauf, known for creating the brand identities for Roots, Molson and Toronto Life magazine, called on Kunz to render German war criminal Helmut Rauca. Rauca, a former SS Master Sergeant charged with killing over 11,000 Jews, was living freely in Toronto by the early ’80s. Kunz showed him as a skeleton twisted in the shape of a swastika and balancing the scales of justice filled with hands reaching up for help. More work from Fishauf and additional praise from New York artist Marshall Arisman in a Communication Arts article soon opened the doors to so many assignments from Canadian and American publications that, until two years ago, Kunz maintained an apartment in New York in addition to her home base in Toronto.

Photographed in her studio in Cabbagetown, Toronto, March 2016. While she’s still a sought-after artist, Kunz says she’s had to adapt her strategies when it comes to getting new work. “There are a lot of great artists out there; there just isn’t the work that there used to be,” she says. “I wish I had the jobs that I used to turn down. There was so much work and so many fewer artists.” Right opposite her drawing board, Kunz installed a wall-mounted TV set to stream CNN. Some artists would consider that a distraction. For Kunz, it’s food for thought.

Photographed in her studio in Cabbagetown, Toronto, March 2016. While she’s still a sought-after artist, Kunz says she’s had to adapt her strategies when it comes to getting new work. “There are a lot of great artists out there; there just isn’t the work that there used to be,” she says. “I wish I had the jobs that I used to turn down. There was so much work and so many fewer artists.” Right opposite her drawing board, Kunz installed a wall-mounted TV set to stream CNN. Some artists would consider that a distraction. For Kunz, it’s food for thought.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Kunz rode the celebrity culture wave doing portraits of Hollywood actors and monthly end papers on the history of rock and roll for Rolling Stone. She also drew over 50 book jacket covers and took on the occasional advertising assignment for beer brands and chocolate companies, although working in advertising was never her goal, even if the money was amazing.

September 11, 2001 changed everything, but for illustrators it hit the tone and volume of their assignments. Before that, you could be more biting and controversial in print, says Kunz. “Darker work was being widely published.” She points to the moment President George W. Bush declared, “You’re either with us or you’re with the terrorists” as the turning point when political commentary and satire practically evaporated, with The New Yorker being the only exception.

Since then, the aftershocks of 9/11 have been replaced in publishing by the pain of a broken advertising model that has drastically reduced the power of print, scattered readers across the Internet and forever changed the way all commercial illustrators must work. “In the old days, we would enter the awards annuals or buy a page in Workbook or Showcase and sit back and wait for an art director to phone us. But very few of us rely on commissioned work anymore,” says Kunz. “That strategy is obsolete.” Instead, everyone now is focused on self-generated work. Kunz has even taken to calling herself a “content provider” for the print publications that are left.

With a wall of awards to her credit—including Officer of the Order of Canada, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal, honorary doctorates from OCAD University and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and now a Golden AACE Image Award—the biggest highlight of Kunz’s career is still the opportunity to travel the world, including a jaunt to Spain last fall where she met up with her pal, Ralph Steadman. “I never saw travel as being part of my job. I thought I’d just be in my studio working away,” she says—but Kunz gives workshops, lectures around the world and regularly attends international cartoon conferences. “Just being able to see how artists work in other countries [is really eye-opening]. Through my travels, I’ve met artists from Iran, China and Cuba and they’re so amazed by our [autonomy and] freedom of speech. It’s something most of us take completely for granted.” But not Kunz.

Anita Kunz and Ralph Steadman overwhelmed by the beauty of Spain.

Anita Kunz and Ralph Steadman overwhelmed by the beauty of Spain.

Feminist

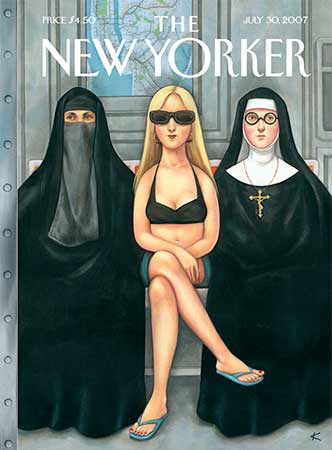

“Girls Will Be Girls,” The New Yorker, July 30th, 2007. “The covers editor at The New Yorker is Francoise Mouly,” says Kunz, “and she’s married to the artist, Art Spiegelman [of Maus fame]. Mouly is amazing to work with. Like most French people, she loves comics, cartoons and all kinds of art, and she makes sure that she uses a lot of women illustrators. Diversity with her artists is a big deal. I’ve sent her all kinds of stuff that I know will never make the cover, but she’s really open to pretty much everything. And she never censors me at all.”

“Girls Will Be Girls,” The New Yorker, July 30th, 2007. “The covers editor at The New Yorker is Francoise Mouly,” says Kunz, “and she’s married to the artist, Art Spiegelman [of Maus fame]. Mouly is amazing to work with. Like most French people, she loves comics, cartoons and all kinds of art, and she makes sure that she uses a lot of women illustrators. Diversity with her artists is a big deal. I’ve sent her all kinds of stuff that I know will never make the cover, but she’s really open to pretty much everything. And she never censors me at all.”

Canadian

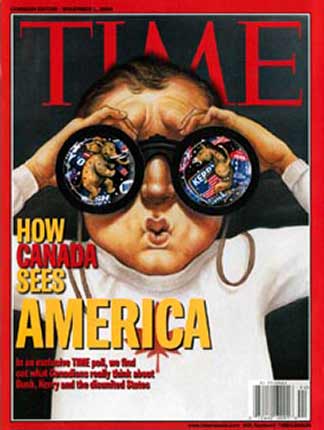

“How Canada Sees America,” Time (Canadian Edition) Nov 1, 2004: “It used to be that there was a hierarchy of magazines and if you did a Time cover you were the best artist. But now, with the Internet, it just works in so many different ways to get your work out there and it isn’t as binary. That’s one of the biggest changes from 20, even 10 years ago.”

“How Canada Sees America,” Time (Canadian Edition) Nov 1, 2004: “It used to be that there was a hierarchy of magazines and if you did a Time cover you were the best artist. But now, with the Internet, it just works in so many different ways to get your work out there and it isn’t as binary. That’s one of the biggest changes from 20, even 10 years ago.”

Book Covers

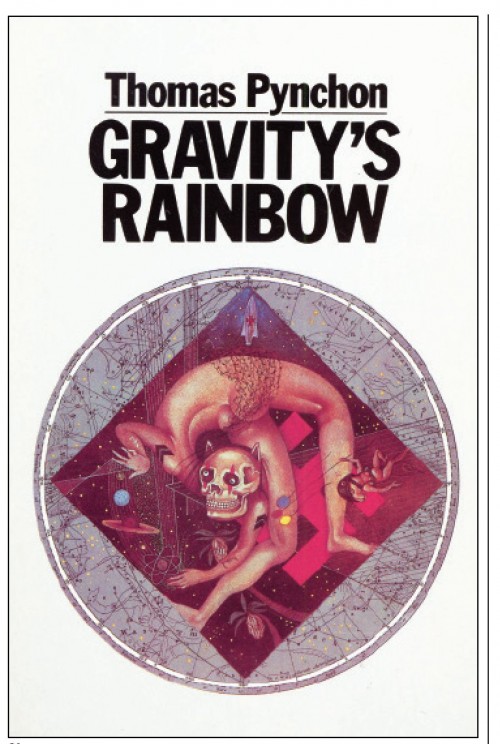

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon, 1984, Picador Books: “This was one of the most complicated books I ever read, and really hard to get the germ of the idea. Pynchon kept going off in tangents. I mixed up the art the same way the writer did and made an image that can be read in all directions.”

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon, 1984, Picador Books: “This was one of the most complicated books I ever read, and really hard to get the germ of the idea. Pynchon kept going off in tangents. I mixed up the art the same way the writer did and made an image that can be read in all directions.”

Allegories

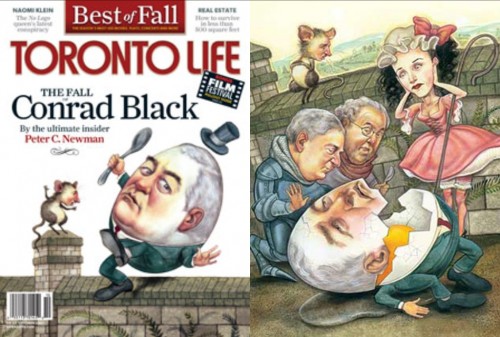

“The Fall of Conrad Black,” Toronto Life, Fall 2007: Kunz often uses word associations and lateral thinking to find ways to visually explain events in the news. She especially likes to refer back to older works in literature or art history to give these events a context. To wit: Conrad Black as Humpty Dumpty having a great fall, Lance Armstrong as Pinocchio riding a bike and Trayvon Martin as Munch’s Screamer in a hoodie.

First Big Break

Helmut Rauca, Saturday Night, 1982: “The Rauca piece was one of [my first significant] assignments. The angle of the article was, there’s a monster living among us and no one has ever done anything about it.” Rauca was an S.S. Master Sergeant during the Second World War who moved on to a quiet life in Canada.

Helmut Rauca, Saturday Night, 1982: “The Rauca piece was one of [my first significant] assignments. The angle of the article was, there’s a monster living among us and no one has ever done anything about it.” Rauca was an S.S. Master Sergeant during the Second World War who moved on to a quiet life in Canada.

A version of this article originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of Applied Arts Magazine.

Drop cap by Jessica Hische, courtesy of Daily DropCap.

Leave a Reply