This is it

August 18, 2016

Cleaning up the remains of our parents’ days has been a long process for my brothers and me. Five years to be exact.

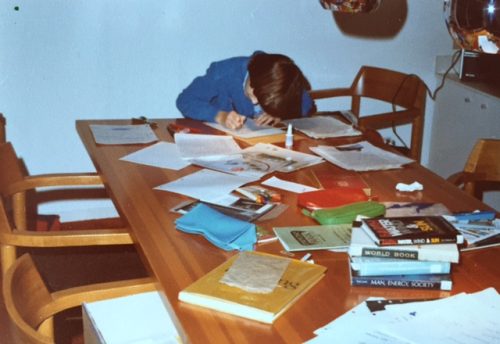

From left to right: Alison, Richard and Peter. We’re probably watching Wimbledon or the U.S. Open.

From left to right: Alison, Richard and Peter. We’re probably watching Wimbledon or the U.S. Open.

Yesterday, as I was studying the photographic evidence of our childhoods inside a non-descript industrial storage unit, I experienced a sense of peace and order I wasn’t expecting and haven’t truly felt since the days when orbiting the very alive Catherine and Trevor was the only way of being the three of us knew.

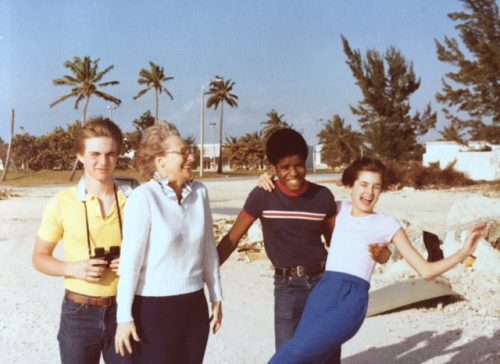

There she is, the dynamic Catherine Garwood-Jones with her kids. Photo by Trevor.

There she is, the dynamic Catherine Garwood-Jones with her kids. Photo by Trevor.

And here I am today living in that future that the wee, then lanky girl in the photos was being groomed for. This was before she knew what form it would take. I’m sure my brothers are also flipping back and forth between past, present and future. I’ve read enough “Passages”-style pop psychology to know that we all think about this stuff.

Those books and magazine articles said that the moment would arrive when you realize that the bright future that was once so far ahead of you is officially more behind you. It’s like crossing the continental divide. I did that in a riverboat tour on the Danube with my dad six months before he died. The captain of the ship blew the horn and let us know when we had ceased our connection to the land and were now officially being drawn towards the open ocean.

I share this not to bring myself or the reader down. I’m writing it because it reinforces something in me that has been the only information I’ve ever had about the world. And now I know why.

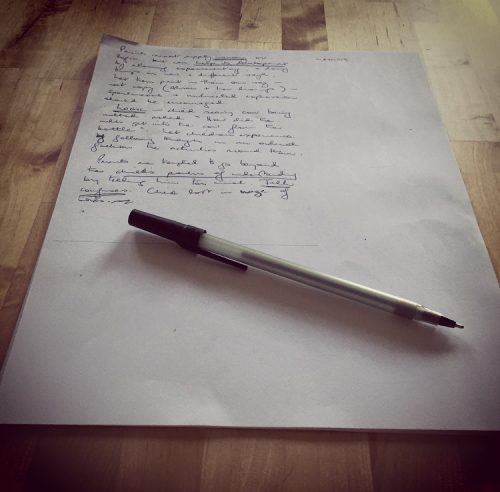

Yesterday, during our organizing session, my brother placed in front of me a stack of notes in our mother’s handwriting.

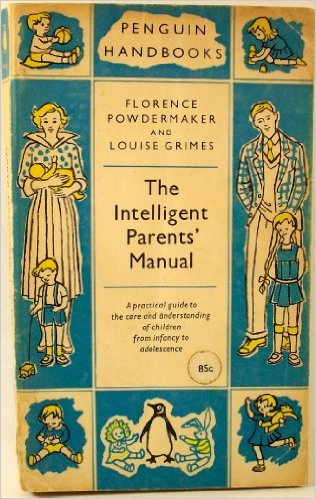

At some point, forty plus years ago, she thought it important to organize her thoughts on the best way to raise secure, independent children. Some of it sounded like her voice, the rest read like a textbook or a medical journal. A quick Google search showed that she was pulling ideas from The Intelligent Parents’ Manual, by Dr. Florence Powdermaker and Louis Grimes. Can’t you just see them in their clinicians’ jackets? Such models of medicine and home economics! Having lived in London, England throughout the 1950s in a flat lined with beige and orange Penguin classics, I’m guessing that our mum had the 1956 Penguin edition (the cover art is charming).

Powdermaker and Grimes’ book is now out of print. This is the 1956 Penguin edition.

Powdermaker and Grimes’ book is now out of print. This is the 1956 Penguin edition.

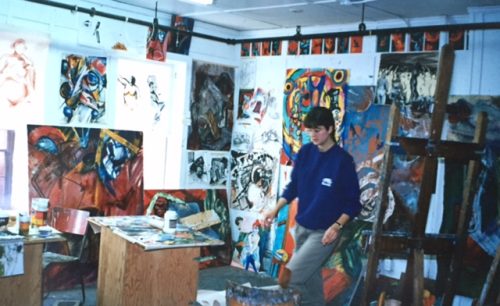

But beyond the Penguin cool factor, what truly caught my breath was coming upon the phrase, “Alison and her drawings” inserted into a paragraph about art and storytelling. Finding a parent referring to you, years after they have died, gives you an unexpected new wave of love and encouragement from them you weren’t expecting on your average Tuesday.

“Allow experimenting and doing things in new and different ways,” wrote the authors, and so transcribed my mother. “Let them paint in their own way instead of always imitating others and sticking to the hidebound, conventional ways. Let them paint what they desire instead of copying some model that may mean little or nothing to him. “[Alison and her drawings]. In music, drawing and storytelling, the child’s own spontaneous and undirected expression should be encouraged.”

I suspect my mother’s own good instincts on how to encourage children (and people of all ages, for that matter) were there all along and only reinforced by this book. Hence the notes.

I was so glad my brother found this stash at a time when all three of us are looking towards the open ocean. I’m handling the waters by writing, drawing, canoeing, pulling my friends closer, eating more expensive cheese and artisanal olives, and searching for poems and biographies that describe the thick stew of emotions that form after you lose both parents. For whatever reason, fiction is leaving me cold. This stew has sometimes slowed me down to a crawl on par with folks much, much older than I am. My sluggishness and hazy contemplation are completely at odds with the frenzied, convulsing and not particularly welcoming workforce we’re all participating in right now. It’s not something you can really explain to others.

Being reminded by my mother in notes taken over forty years ago that I need to “experiment and do things in new and different ways, and portray what [you] desire,” compels me to get back to the unconventional path that has me steering myself somewhere between writing, drawing and teaching, all the while paying no mind to convention.

I was. She saw. Hence, I became.

Leave a Reply