Her name was Paraskeva

October 25, 2021

Last week, this Jane Goodall quote was trending on Instagram and LinkedIn: “It actually doesn’t take much to be considered a difficult woman. That’s why there are so many of us.”

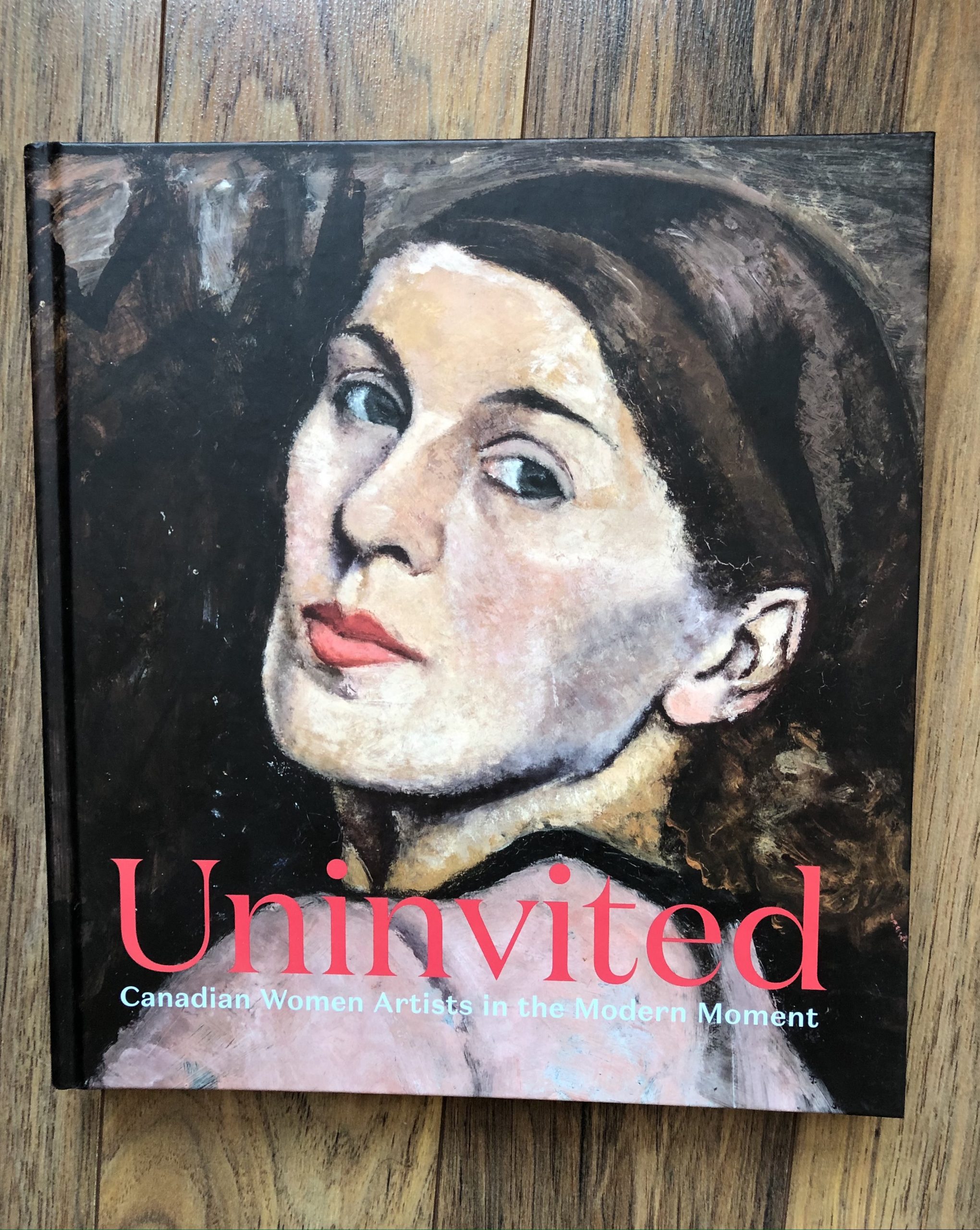

Meet Paraskeva Clark, a Canadian painter with a Russian purr whose portraits dared you to blink first. Paraskeva’s self-portrait was chosen for the cover of Uninvited, the stunning exhibition featuring 20th century Canadian Women Artists now showing at the McMichael Gallery in Kleinberg.

Holy Hannah, it’s a good show.

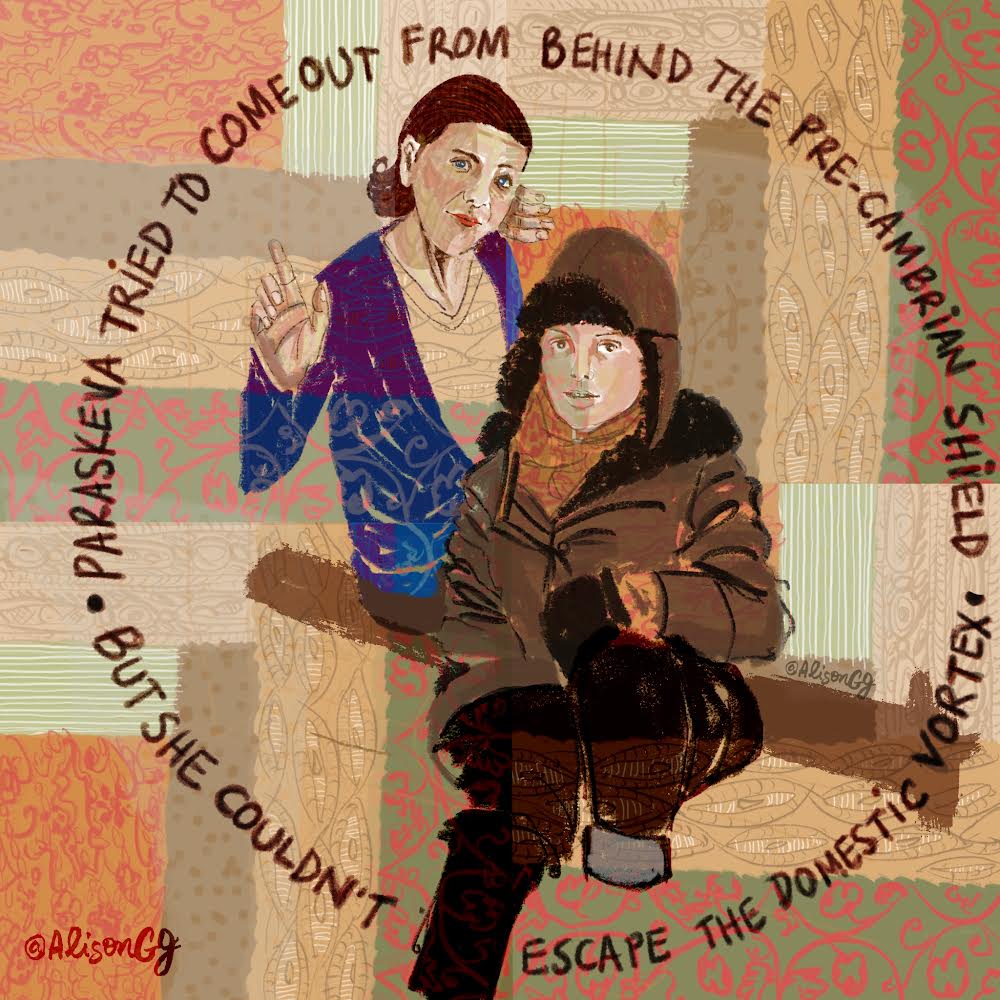

Here is my interpretation of Paraskeva’s life.

“Come out from behind the Pre-Cambrian Shield.”

It took an outsider to issue this challenge to Canadian artists to expand the repertoire of our art beyond rocks, trees and brute strength to something more psychologically challenging.

The year was 1937 and the challenger, Paraskeva Clark, was a gimlet-eyed emigrée steeped in Russian literature, French cuisine, and the social tensions that boil over when the haves take too much. It’s not really surprising that women in Canada, like Paraskeva, felt compelled to take on portraiture and social subjects with greater gusto than the guys. Their lives raised different — and sometimes more insidious — questions and sacrifices that never touched middle class male privilege.

In the years before and after WWII, what was acceptable for a settler woman (of some means) to want and do expanded and contracted rather dramatically. In Paraskeva’s case, the ferocious artistic ambition she brought to Canada from Paris by way of St. Petersburg had curdled into ferocious resentment after she agreed to take on marriage and motherhood in the staid metropolis of Toronto. So what if she had an accountant husband and a nice home in Forest Hill. Her days still became, as she said, “cooking, cooking, cooking. Loblaws, Dominion; Dominion, Loblaws … “

Her entire life, she was also the primary caretaker for her oldest son who lived with Schizophrenia. Love and devotion to her husband and sons co-existed with a powerful resentment that women had to accept their lot in the home. She resorted to hurling insults at the Group of Seven members. “What do they know about menstruation?”

By the end of her life, her manifesto had shifted from art to gender roles.

Paraskeva could be a downer, deflating, with her Russian purr, the artistic dreams of younger women coming up. Don’t do it, she essentially told them. “The whole history of painting is against women painters. … Her physical and mental makeup is not suited to gather [the] forces necessary to produce a really important works of art.”

She never could bring herself to say “our physical and mental makeup is not suited to producing really important works of art.” She was too proud to include herself in that defeated cohort. Who knows, maybe she was holding out hope for a string of final masterpieces in her spare time.

Of course, what she was really saying was that women can’t shut out interruptions the way men can. Men’s increased participation in the home was still decades away. “What’s a woman’s fate? What has the Lord created us for?” she challenged, waiting to tell us. “Just to produce more men. I can’t forgive him for that.”

Paraskeva was a bundle of contradictions, but she looked eveyone squarely in the eye and somehow made them smile, sit up taller and question why things are the way they are.

It doesn’t seem outrageous to imagine Paraskeva today in one of her hats winding her way through crowds, online and offline, calling for men to #ShareTheBurden and for Canada to show its struggles. She would have been a force on Twitter, speaking truth to power as only she could.

Leave a Reply