Her Last Photo

September 12, 2022

Queen Elizabeth II: 1926-2022

Her smile was the same. Those girlish pointed canines that thousands of royal banquets and teeth-grindingly close horse races had never worn down.

The eyes were the same, merrily locking with the camera lens as if Cecil Beaton — her mother’s favourite camera-toting popinjay— had just zhuzhed up the flower arrangements and poked the fire into a roaring blaze.

The hunch was deeper. That still felt painfully new.

But it was the backs of her hands that announced the end was nigh.

They were an alarming deep purple, a colour that intensified the solitaire sparkle of Philip’s devotion, shining like a dying star on her left hand.

That got brighter on her way out.

It is these universals that inconveniently gloss over the centuries of arrogance and entitlement that the role of Monarch embodies.

It is why people, like me, with parents who were her exact contemporaries — he from England, she from the Cape Colony of South Africa, where Princess Elizabeth gave her famous 1947 “whether my life be long or short” radio address — have felt weepy these past few days.

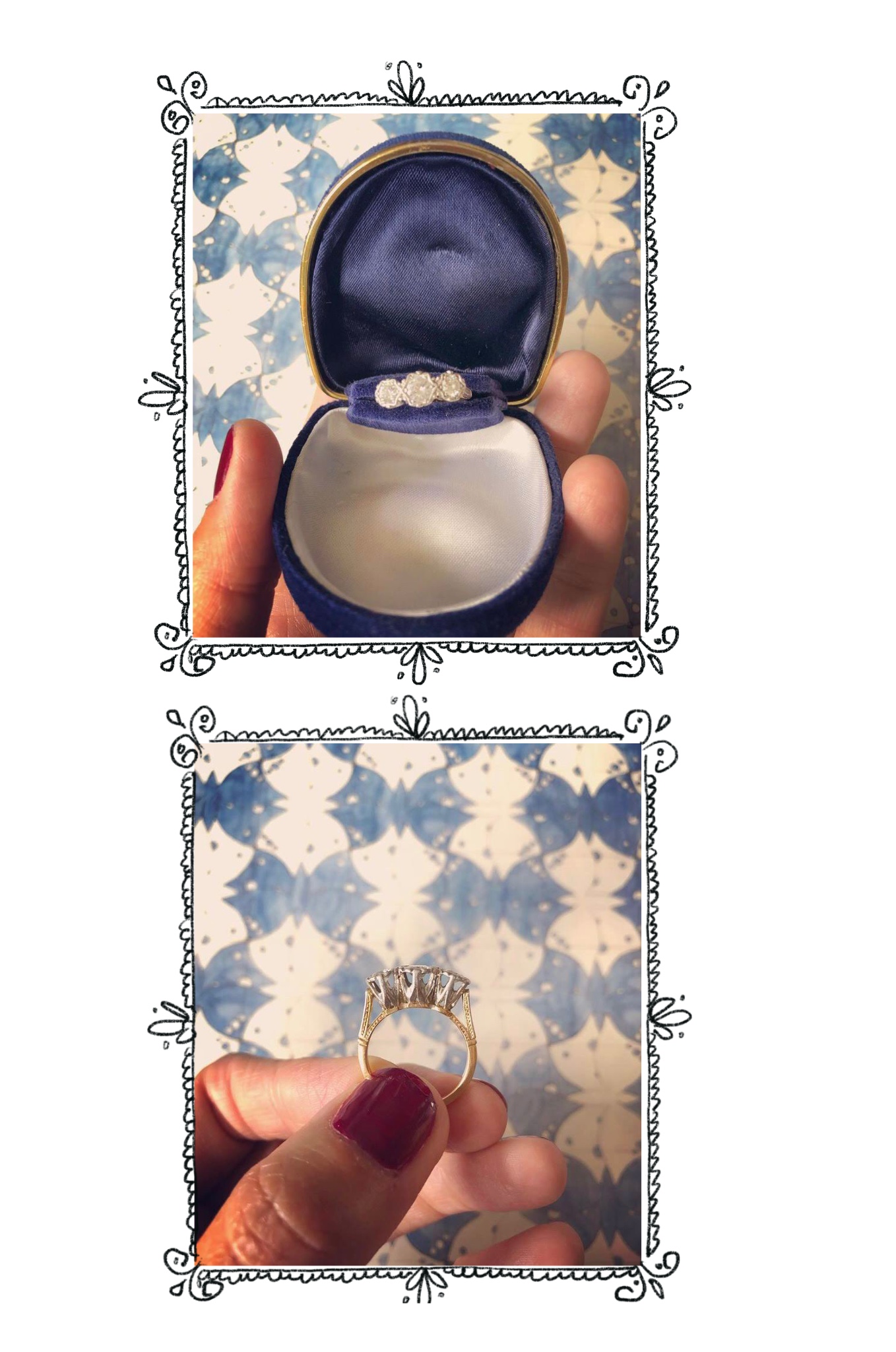

It is these universals that make me slip on my mother’s engagement ring, custom-designed in London in 1949 by a pipe-smoking architecture student.

His sketches hoisted three very decent-sized diamonds atop a system of flying buttresses as breathtaking as Canterbury Cathedral, which he visited on his motorcycle during several thesis research trips. Mum typed up his final thesis comparing English and French Gothic architecture.

For a nation and a bombed-out city that was still rationing milk, lard, eggs and chocolate, its young men refused to cheap out on diamonds. Meanwhile, ridiculously practical women like my mother were ok with that.

As with the death of a Queen, sometimes in life we look the other way and just feel.

Leave a Reply