Out of sight

April 7, 2011

Updated on April 10: scroll to bottom

I spent four years at Queen’s University shouting in Gaelic at football games, waiting in line at the campus pub and preparing for slide tests (I was an art history major). In between socializing, two ideas mentioned in passing during my painting seminars shot up like flares:

Men look at women, whereas women watch themselves being looked at.

Men look at women, whereas women watch themselves being looked at.

John Berger wrote this line in the must-read Penguin classic, Ways of Seeing, and I’ve yet to find a more astute commentator on men’s and women’s different experiences with just being. These social differences — I Woman/You Man: So, what’s it all mean? — were the most compelling reason I started this blog. I like trying to decode the sexes.

Being a woman, I’m hyper self-aware the moment I step outside. People’s reactions to me make my eyes and brain do 180° panorama shots of my surroundings. Sometimes I feel in control. Last night was not one of those times. I got off the streetcar well before my stop because a guy started owning me with his stare. I know the difference between an appreciative glance and a sinister stare. When I got on the car, this guy sitting at the back walked up the aisle and sat in the empty seat next to me and started leaning into me, boxing me in at the window. I waited about ten seconds (an eternity), then rang the bell, got off and heaved a sigh of relief when the streetcar took off with him still on it. Anthropologists study this sort of dynamic between lions and gazelles. You better hope the gazelle can run fast because re-socializing all the lions is complicated.

A lion has his way with a gazelle.

A lion has his way with a gazelle.

Just ask Jane.

She’s got the look: Jane Goodall watching primates in the African jungle.

She’s got the look: Jane Goodall watching primates in the African jungle.

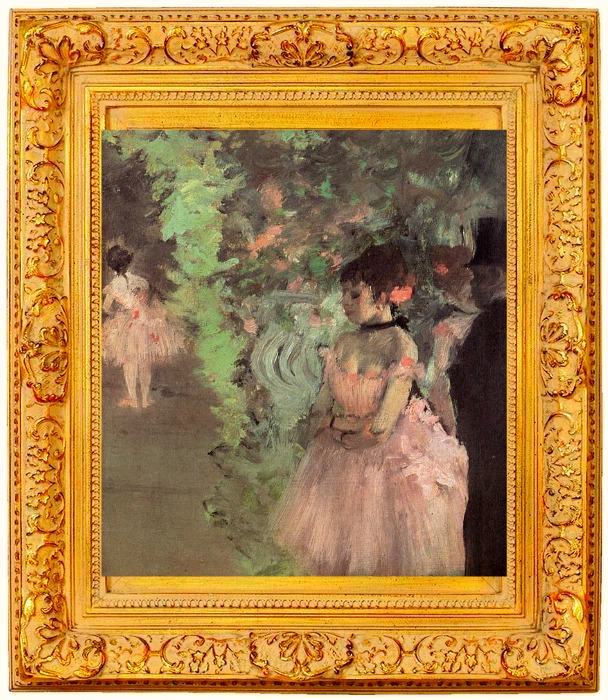

Berger’s ideas on looking came up during one of my university seminars on Degas’ ballet paintings. Our prof wasn’t showing us the artist’s paintings of ballerinas at the barre — you know, those colourful blurs of white tulle cinched by red and blue sashes that send museum gift shop managers into buying frenzies. Nuh-uh, we were looking at Degas’ sooty oil sketches documenting the underbelly of the dance world, where men lurked backstage in order to watch and make their choice of kohled and rouged-up pre-teens before the girls burst onto centre stage. This one came up:

Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage, 1872 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Edgar Degas, Dancers Backstage, 1872 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

This basic dynamic — men look at women whereas women watch themselves being looked at — isn’t something that feminism has reversed, or can necessarily correct. “Women have a different social presence than men,” Berger explains. Here’s what he means (now try applying this to all the powerful and charismatic men you know):

A man’s presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies. If the promise is large and credible his presence is striking.

Steve McQueen stepping out.

His promised power may be moral, economic, social or sexual — but its object is always exterior to the man. A man’s presence suggests what he is capable of doing to you or for you (even if he pretends to be capable of what he is not).

By contrast, a woman’s presence expresses her own attitude to herself, and defines what can and cannot be done to her. Her presence is manifest in her gestures, voice, opinions, expressions, taste and clothes.

Should we protest this? Hell yes, especially the what-you-wear-and-what-can-be-done-to-you part. Last week’s Slut Walk in downtown Toronto was an attempt to re-socialize and educate the lions. But, wow, what a neverending battle we’re facing. We’re always two steps behind human nature’s driving instincts. Berger goes on,

Presence for a woman is so intrinsic to her person that men tend to think of it as an almost physical emanation, a kind of heat or smell or aura.

Ruth Orkin, American Girl in Italy, 1951

Ruth Orkin, American Girl in Italy, 1951

(And here I’m paraphrasing): To be born a woman means existing within an allotted and confined space [I definitely felt that on the streetcar]. The social presence of women has developed as a result of their ingenuity in living within such a limited space. But in doing so, women have had to split themselves in two. She must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself. If she is walking down the street, she can scarcely avoid envisaging herself walking down the street. Since childhood she has been taught to survey herself continually.

Is it any wonder so many women are completely obsessed with body image? (media pressures aside)

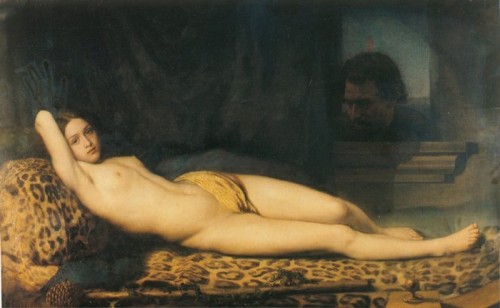

Surely the most blatant example in the history of painting of this notion, Men look while women watch themselves being looked at, is this:

Felix Trutat’s Reclining Baccante, 1845

Felix Trutat’s Reclining Baccante, 1845

The second idea that made me think so hard, first as a student of art and now as a student of life, was the 19th century notion that:

“Women who read are dangerous.”

Vittorio Matteo Corcos, Dreams, 1896 (National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome)

Vittorio Matteo Corcos, Dreams, 1896 (National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome)

This idea was a well-known “rule” in 19th century etiquette books. The thing about reading was that it made women unselfconscious and completely caught up in alternate realities. It made them forget their bodies and their place in the social order, all of which threatened to upend the desired domestic order. Women who sat and read books alone in public spaces, like park benches, became just as suspect in the 19th-century as those who sat alone drinking absinthe in seedy bars. Reading and drinking came to be seen by men as a front for a pick up. Any women who feigned interest in the written word was surely looking to go where angels feared to tread. Men took it as an invitation to hassle, make lewd comments and proposition, while other women hissed their disapproval.

Most readers had no choice but to seek out quiet, protected corners:

Peter Ilsted, Interior with a young woman reading, 1908 (private collection)

Peter Ilsted, Interior with a young woman reading, 1908 (private collection)

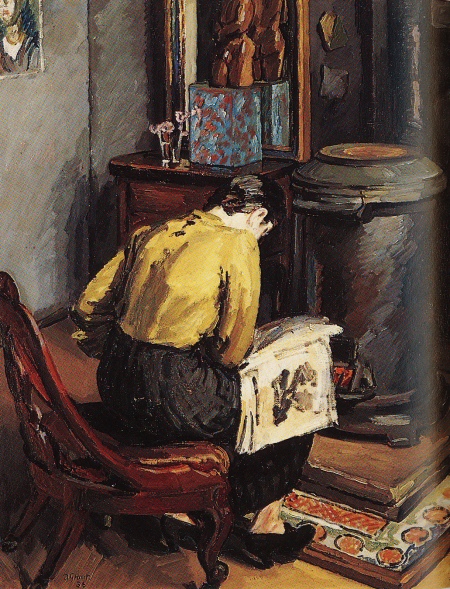

Duncan Grant, The Stove, 1936 (private collection)

Duncan Grant, The Stove, 1936 (private collection)

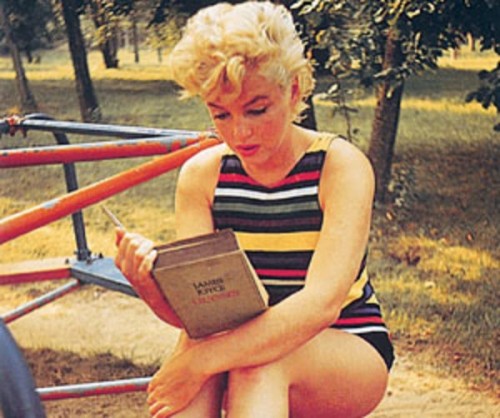

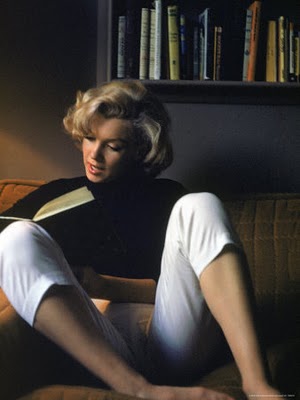

This discussion reminds me of that famous photo of Marilyn Monroe from the late fifties that shows her at a playground, sitting on a merry-go-round in a swimsuit, her head bent over a copy of Ulysses.

Who actually believes she read James Joyce? Or Dostoyevsky? (Well, she did). And, c’mon, what was she really doing there on that merry-go-round? My guess is that she was waiting for the photo shoot to be over so she could get her cheque, go home, kick back and actually read those novels.

In public, at least, Marilyn’s beauty cancelled out the possibility she could ever be focused on anything other than herself. In other people’s eyes, if she was out and about she was courting attention. Marilyn may not have seen it that way — especially when she covered her head in a kerchief and sunglasses — but it doesn’t matter. She was outnumbered.

Sitting in the reading room of the campus library at Queen’s, with a stack of seminar handouts to go through, I always sensed that while some opportunities had opened up for me and my friends, other forms of discrimination hadn’t changed. Required readings often went out of focus the moment I acknowledged a stare from the jock in the next carol over. That could be fun on a Friday afternoon when I was feeling carefree. During midterms it was a different story. If the guy wouldn’t let up, it was always up to me to move. Sometimes, I headed straight for the stacks to avoid the stares. There in the basement I could read, think and drop down inside myself without being on display. Like most women, I wanted to control when and how I was looked at. That’s still a tall order.

It was while I was moving between the stacks and the reading room that I realized, but couldn’t quite articulate at 19, that integrating the two sides of myself — the thinking and the pleasure seeking — was going to be a challenge both for me and for the guys I liked (“So how are we supposed to know when you want to be watched and when you don’t?” they asked. “I’ll tell you,” I said. The good ones always listen).

By graduation, I realized something else: it made no difference that women had been officially admitted to the library and Queen’s University in 1942. Five decades later, beauty and knowledge still felt segregated. It made me think that feminism’s strength was in opening up where women could go, but not in altering the signals we received once we got there.

I decided to write this post when my friend, Danja, a stunning U of T undergrad doing a double major in sociology and philosophy, said she couldn’t get her course reading done at the library. “It’s better if I stay home,” “Why?” I asked, knowing full well the reason.

Just added: Virginia Heffernan (@Page88) takes on the concept that women who read are dangerous (or depraved) in an op-ed piece in April 10th’s New York Times.

Novels, now a signature pursuit of the sound and literate mind, have also [like the internet] been considered toxic, as in the 1797 analysis, “Novel Reading: A Cause for Female Depravity.” The 18th-century worry about female literacy is not unlike the contemporary anxiety that Web use makes girls vulnerable to predators: “Without this poison instilled, as it were, into the blood, females in ordinary life would never have been so much the slaves of vice.”

Berger's "Ways of Seeing" was required reading for a women's studies course I took during my undergrad; it takes me back, and certainly makes me think. Great article, and sorry to hear about the freaky guy on the streetcar–I can absolutely relate!

An unexpected delight to see these two ideas linked. I've been focusing a lot on objectification lately, and trying to untangle its uncomfortable relationship with feminism. Because I think you're right: It's not something feminism can really "fix," in part because so many women (myself included, to fluctuating degrees) are in thrall of the surface benefits of objectification. The cognitive dissonance between that and the danger of being a woman who reads is related to feminism–but in that Frenchy de Beauvoir way, not in the way that most Americans understand feminism.

I found this blog because I was looking for references to "Reclining Bacchante" and was pleasantly surprised to find your work. I write on how we form our concepts of beauty; most recently I've embarked upon a monthlong abstinence from mirrors, in order to tease out these very issues. It's here, if you're interested:

http://jezebel.com/5797742/why-im-not-looking-in-…

Autumn, I'm thrilled to find another searching mind on this topic. Thanks for stopping by and for taking the time to leave a note. I look forward to following your insights during your mirror-less month. I think giving up mirrors is like giving up TV. After a while, you don't think about them anymore or miss them much. Mind you, I have short hair (low maintenance) and can put on my lipstick blindfolded. Stay in touch!

Oh, and this might interest you too: https://alisongarwoodjones.com/2011/02/hubba-hubba…

Al. Great article. The history in and of the paintings and photo's is something I never thought about. Really good. You have brought together these ideas and ideals in very well written peace. Being brought up by a strong mother all the boys in our family are truly blessed. We were taught as boys to care and respect everyone, race, religion, sex, heck we brought friends home in the 70"s that were gay. All were welcome. She told us that is was easy to hate and laugh and make fun of but it took real courage to care. God bless our mom. God bless her love. Wish there was more like her. Thanks for the wonderful article. Garson