… but every now and again something sticks. Thanks guys.

Daddy’s little girl

May 2, 2012

Someone grab the shepherd’s crook and pull this girl off stage.

©AGJ on PicMonkey.com

It’s too late to take back the message

It’s already out

And archived in perpetuity

I can’t even crop you,

You’ve taken over my web page too

If video killed the radio star,

The internet kidnapped daddy’s little girl

Sorry Wayne & Janet

You can’t get her back

That heart-to-heart about social media tanked

She’s back on Twitter

Hanging off the yo-yo boys,

Skating to where the puck is headed, not to where it’s been

And adding filmy veils on Instagram

This must be how Patty Hearst‘s parents felt

Dearest Paulina:

You choose this and you can never go back to that

Not when you’re female

Feminism can’t fix everything

It sounds so archaic, this idea that girls who do it are doomed

But something does die

Even in 2012

A sense of hope and potential

Of fresh starts

Of humanity prevailing

Poor judgement and its consequences used to be sent to the next town over,

Then reinvented in sweater sets somewhere else

Now poor judgement parties in that town’s central square

With cameras catching it from every angle

Wait, is that Charlie Sheen on the Jumbotron?

He knows you, y’ know

And he’s coming over to say Hi

…

The world gets in SUCH a frenzy over PYTs, doesn’t it?

Twas ever thus

It takes vigilance for a young woman to decide, then convince the rest of the world she’s real

Particularly when a Barbie physique comes naturally

It’s easier to cave into stereotypes when everyone wants it that way

It’s millions of them verses one of you

They look

You notice

It’s intoxicating

‘Who needs college or an unpaid internship or a serving job when I’m all this?’ you’re probably thinking

So you get to work at your first big job out of puberty

Posing

You sit up and arch

Lie back and pout

Aviators slipping down the slope of your nose

Or a pair of Buddy Holly’s when the look calls for something more academic

A few seconds pass and someone with your worst interests in mind hands you a pop song you can lipsync

You do your best to be your worst

Add a little dance number

Something metaphorical of you circling the drain in heels

They teach metaphors in college English classes, you know

Same with clichés

And dénouement,

That inevitable downslide after your peak is reached and we’ve all climaxed

Get your Wooos! in now while you still can

*For more on this “hot” topic, see this story in Maclean’s, “Outraged moms, trashy daughters,” by Anne Kingston. And for one of my earlier rants on the topic, go here.

#FreedomIsBlogging

April 30, 2012

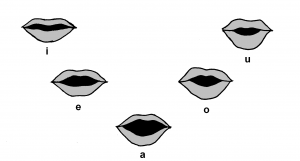

When it comes to blogging, my mental trajectory over the last couple of years has looked something like this:

Looking back, I’d love to say I was an early adopter. The truth is, I arrived late to the social media party and hardly mingled when I got there, choosing, instead, to mope alone in a corner nursing my cup of dread on the rocks. I couldn’t stop thinking about how my existence as I knew it was over. Like, forever.

Looking back, I’d love to say I was an early adopter. The truth is, I arrived late to the social media party and hardly mingled when I got there, choosing, instead, to mope alone in a corner nursing my cup of dread on the rocks. I couldn’t stop thinking about how my existence as I knew it was over. Like, forever.

As with most journalists who had tasted some success the old way, I was suspicious and resentful when all of these seemingly stupid new platforms started taking time, attention and funding away from real reading material — i.e. newspapers, magazines and books.

How was I going to be an OpEd columnist now when newspapers were hemorraging so much of their influence and advertising dollars?

Finally, I said to myself (in this order):

1. Snap out of it

2. Adapt or die

3. And flee into the future as fast as you can

From then on I entered a brand new headspace, one in which I spent countless hours trying to figure out the difference between wasting time and revolutionizing the way I wrote and did business.

Slowly, that old feeling that blogging was something I did under duress (and for free) was replaced by a new sense of excitement and possibility. My penny-dropping moment came when a friend said, “Blog what you want to be known for.” The same goes for tweeting. So I started writing what I wished editors would assign me, but weren’t. In short, I took control of my ambition.

Sure enough, editors started reading my blog. So did filmmakers and designers and corporate types who thought I handled social media well, and why wasn’t I teaching workshops on it to the uninitiated? All of them offered me writing work or paid speaking engagements, which is to say, my blog is now playing a significant role in covering my food and rent. And I’m doing it all on my own terms, without sacrificing my integrity or sabotaging my talent or adopting a photogenic cat. Sorry, I’m a dog person.

So when Hugh MacLeod published his latest book this week, a funny and insightful collection of essays called Freedom is Blogging In Your Underwear I read it as a true believer.

“Having a blog, a voice, having my own media, utterly changed my life,” says MacLeod.

Mine too. “Having my own media” … hmmm, take note of this concept, fellow journalists and novelists.

“That’s what the Internet is REALLY about,” continues MacLeod. “Finding your freedom. Finding your wings. Using a computer instead of a guitar.”

Blogging is the new rock and roll.

You, me, we’re all on one end of the wire, MacLeod concludes. “But worry less about the wire,” he warns. “Worry less about the shiny objects in the middle [Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, blah, blah, blah], and, instead, think about MAKING your own stuff, and the rest of the Internet will look after itself.”

And you.

#FreedomIsBlogging

Pink snow

April 26, 2012

“Last week the cherry blossoms were falling all over the city, and children chased them in the same way they chase snowflakes. The most spectacular drifts of this pink snow were to be seen along Park Avenue, where cherry trees line the center island, and speeding cars cause the petals to swirl and dance.” — Bill Cunningham, “On The Street,” The New York Times (Sunday, April 22, 2012)

Hot off the press

April 19, 2012

My latest article …

The healthy house

Photography by Shai Gil

Four years ago, when Toronto’s Superkül transformed a derelict blacksmith’s shop on a narrow city laneway into a sustainable single-family home, the firm’s preservationist aesthetic went viral with design critics and tree huggers alike. With their latest residential project, in rural Ontario, principals Andre D’Elia and Meg Graham faced a whole other set of limitations: their client lives with acute sensitivities to dust, pollen, electromagnetic radiation and a long list of construction materials, rendering any chance of building in a conventional manner virtually impossible. The result is +House, a two-bedroom dwelling nestled between a hill and a pond that has set a new precedent in Canadian environmental design.

Call it signature Superkül: this cedar- and teak-clad house in Dufferin County, two hours northwest of Toronto, is compact, low lying and well lit, with full-height windows that open up the residence’s entire 82‑metre length. As with many of the firm’s other projects, a green roof perforated with skylights pulls in additional light and air.

But before principal Andre D’Elia fired up CAD, he and project architect Geoffrey Moote spent hours determining what constitutes a healthy house. With the client’s input – “She knows what she can and can’t tolerate” – they quickly eliminated drywall compound (dust), paint (gas emissions), and the idea of a basement (mould). They also made a note to install ductwork with hospital-grade filters. To their surprise, they learned that building materials with higher recycled content aren’t necessarily suitable for everyone. “That’s when the juncture between sustainability and health didn’t always jibe,” says D’Elia.

Attaining a LEED rating wasn’t a major concern initially, not when the team was faced with other issues, including sourcing allergen-free materials, implementing healthy installation methods, and finding contractors willing to work on untried ideas. Not until they began to determine what sort of footprint they could make in the hill, without adversely affecting the trees or the pond, did they consult LEED’s checklist of sustainability points. “The project was always more idiosyncratic than just hitting the LEED basics,” notes Graham. “We spent a lot of time couriering the client boxes of building samples so she could pick them up, smell them, and then wait to see if she had a reaction. The results were very specific to the individual.”

Take the countertops: some types of granite and natural rock emit low levels of radiation, and others contain epoxies that didn’t agree with the client, so they turned instead to IceStone, made from recycled glass. For the walls, they used American Clay, a VOC-free plaster that never dries completely and helps regulate the interior humidity and temperature. Choosing the right millwork proved more challenging. They tested over 40 substrates with the client before settling on a white oak veneer, with AFM Safecoat as the sealant. After the cabinetry was built and sealed, it was put in storage for several months, to allow it time to off-gas. Once they installed the cabinets, they brought in ozone machines to blast away any lingering off-gas.

The risk of leaving behind health-threatening toxins after construction raised another issue of what to do about contaminants being inadvertently introduced. Throughout construction, everyone on the project had to abide by the client’s strict site rules, for instance ensuring that they cleaned their spray guns properly before applying the allergen-free sealant; any residue from other products would have sabotaged the site. Walking on eggshells caused a real issue with some of the subtrades. “We went through three electricians before we found one who was willing to wire the place differently,” says D’Elia. “They all said, ‘Look, I don’t want to be responsible for this.’ ”

In their ongoing effort to keep surfaces dust-free, the designers incorporated passive ventilation, using sliding doors to pull in the southwest breezes coming off the pond, then letting them escape through clerestory windows on the north wall and three skylights. During pollen season, the owners can batten down the hatches and turn on the air conditioning. As for the green roof, rather than providing a specific health solution it visually extended the hill over top of the house, like a blanket, and moderated the interior temperature. It is also a surefire way to attract birds.

team was faced with other issues, including sourcing allergen-free materials, implementing healthy installation methods, and finding contractors willing to work on untried ideas. Not until they began to determine what sort of footprint they could make in the hill, without adversely affecting the trees or the pond, did they consult LEED’s checklist of sustainability points. “The project was always more idiosyncratic than just hitting the LEED basics,” notes Graham. “We spent a lot of time couriering the client boxes of building samples so she could pick them up, smell them, and then wait to see if she had a reaction. The results were very specific to the individual.”

Other health measures taken aren’t as visible. D’Elia and Moote came up with a new electrical wiring solution that almost completely eliminates the fatigue-inducing electromagnetic fields. Instead of using plastic-coated wires, they used wires in steel-coil shields and installed them, not by wrapping them in horizontal runs around each room, but by making vertical runs that came up from the floor or down from the ceiling to that one spot where power was needed.

In the end, no one knew how all of the products would react in combination. “Remember, this was a prototype,” says D’Elia, and as far as they know it’s the first new build to incorporate these elements. “It was a nail-biting experience the first time the client walked in,” recalls Graham. “We were like, ‘Oh God, what’s going to happen?’ ”

Now that the owners are happily living in the home – cooking, reading, doing yoga and watching for wildlife – the architects shouldn’t feel shy about running a victory lap or two. But who remains accountable if the project doesn’t succeed over the long term? While no one signed contracts, it was understood that the designers and contractors would do their best to create the most allergen-free space possible. “It’s always about achieving a synthesis of healthy design, sustainability, and what is classically considered ‘high design,’ ” says Graham. “The intention was never to let one suffer forany of the others.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find another contemporary home that meets that mix of criteria. And with allergies and environmental sensitivities on the rise, it likely won’t be the last.

This was published in the May 2012 issue of Azure Magazine

Why some never disappear

April 17, 2012

I am not a grammar geek. I didn’t like Strunk & White’s Elements of Style. Admitting that, I’m told, is a travesty — like not drinking 8 glasses of water a day. I do, however, love everything else E.B. White wrote and said. He feels like a trusted mentor.

“A writer should concern himself with whatever absorbs his fancy, stirs his heart, and unlimbers his typewriter. I feel no obligation to deal with politics. I do feel a responsibility to society because of going into print: a writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error. He should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life.”

“I have always felt charged with the safekeeping of all unexpected items of worldly or unworldly enchantment, as though I might be held personally responsible if even a small one were to be lost. But it is not easy to communicate anything of this nature.'”

“A writer must reflect and interpret his society, his world; he must also provide inspiration and guidance and challenge. Much writing today strikes me as deprecating, destructive, and angry. There are good reasons for anger, and I have nothing against anger. But I think some writers have lost their sense of proportion, their sense of humor, and their sense of appreciation. I am often mad, but I would hate to be nothing but mad: and I think I would lose what little value I may have as a writer if I were to refuse, as a matter of principle, to accept the warming rays of the sun, and to report them, whenever, and if ever, they happen to strike me.”

Hat tip to Maria Popova’s article in The Atlantic.

Typewriter illustration by Alanna Cavanagh

Spotlight: Growing Pains

April 16, 2012

Alice grows too tall for the room, from "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland," 1891 by Lewis Carroll. Illustration by Sir John Tenniel.

SPOTLIGHT is Society Pages’ newest column focusing on questionable occurrences. Read other columns here.

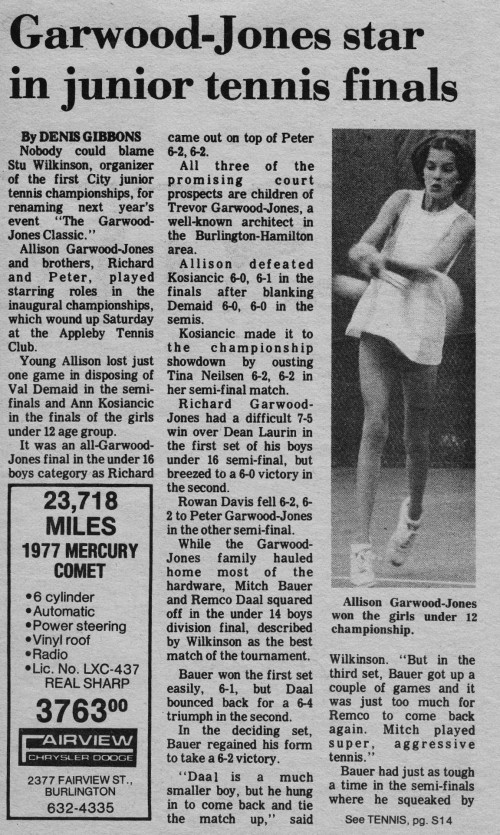

A dozen years ago, when the thought of becoming an academic art historian had lost its luster, I found myself throwing all of my investigative energy into a more personal story. This was back when I was trying to break into journalism, with no degrees or contacts, and pitching stories like, “I grew an inch in a week and, God Almighty, it hurt.” (Aside: it took me another 4 years of pitching and flailing to call myself a journo).

Still, it’s true. I grew an inch in a week and I’ve always insisted that the pain I felt in my spidery arms and legs coincided down to the minute with the moment my limbs were taking off in all four directions. For about a century, though, the idea that kids could feel themselves growing made the white coats smile and shake their heads. As a result, growing pains took pride of place next to the dreaded ice cream headache as these perplexing, slightly silly tales worthy of Newbery Medals, but serious scientific attention? No.

Yeah, whatever. All I know is that after a few years of crazy growth spurts, I crested at 6’1″ by grade 10 and the rush to recruit me to play on the basketball and volleyball teams was on. That happened before it was determined if I had any talent. And I remember thinking, for the first time, how invested everyone seemed to be in the idea that height=power. It’s in our DNA. It’s why tall people are hired faster than shorter ones, and paid more too — except if you’re a writer. Then you sit for most of your life (making you as tall as a child), and take peanuts for pay because you’re powerless to do otherwise. It’s like juvenile detention … the bastards.

I should probably cool it and just tell my story.

As it turned out, volleyball was a natural fit for me since I was good at racquet sports and I loved finishing points off at the net. But basketball was a disaster. For whatever reason, my head and body never came together on the court. Instead, I inspired a wave a snickers in the bleachers for my signature technique. “Windmill arms,” someone shorter and sportier called it. “What …” I stared back with a glare so stern it could have turned our school mascot (a Trojan warrior) to stone. But not the peanut gallery. They just grinned back.

Twenty five years later, I still find myself reading Wikipedia entries trying to understand what centre forwards are supposed to do. Apparently high school trauma never fades.

Here’s how it went down: back in the summer of ’82, when Whitney Houston was a junior model for Seventeen magazine and Princess Di was a walkabout rockstar, I was not so patiently waiting for the transistor radio pressed to my ear to play Men at Work or the J. Geils Band again. I was also completely dreading bed time because it meant another possible invasion of the body stretcher. Friends suggested I was achy a lot because I was playing too much tennis, and my muscles were overworked …

… but, no, that wasn’t it.

For four nights running the ache in my limbs came in waves around 3 am. I remember folding my legs up under my chin and trying to rock away the pain, then stretching them out and rubbing the length of my shins and thighs until I imagined I saw sparks. My mewing woke the entire house, turning my brothers over in their beds and sending my parents from room to room gathering up the necessary rescue gear: two heating pads plus an extra heavy blanket to weigh them down, and a Dixie Cup filled with cool water for taking the aspirin nestled in my mother’s extended palm. Mum and dad always tag-teamed on these nights, taking one leg each. “I’m growing,” I said with the kind of fury women, mid-delivery, save for their husbands (OK, so I exaggerate, but it was intense). Mum and Dad kneaded my muscles and didn’t question the cause. Neither did I.

Every time this happened — I grew over two feet between my tenth and fifteenth birthdays — my dad and I would meet before breakfast the next day for a “height-in,” similar to a jockey’s weigh-in. I’m sure it appealed to the side of him that was into sports stats and breaking records. We used to watch ABC’s Wide World of Sports together, a show that threw in words like “agony” and “human drama” into its classic opening montage, the one with the thunderous kettle drums and Jim McKay’s frantic voiceover accompanying clips of Indy crashes, World Cup wipeouts and Russian weight lifters shaking under barbells bigger than truck tires. At the height-in, Dad would slide a Bic pen over the crest of my skull and carve a blue notch on the wood inside of the cupboard door housing my mum’s winter coats. “Up an inch,” he’d say before carefully writing the month and year beside the notch. Now as my brothers and I start the sad task of cleaning out our childhood home, I wouldn’t mind claiming that door.

If we can feel the push of a new tooth, the pinch of ovulation, and the itch and stab of multiplying cancer cells, why not the accumulation of healthy bone cells as they barrel forth ahead of attached muscles and tendons? This is what I was thinking as I looked for clues in the medical journals stacked up around me. Surfing online pulled up nothing of consequence on growing pains back in 2000, so I relied on actual visits to the University of Toronto’s Gerstein Science Library to find answers.

And here’s what I confirmed: children really do grow at night. The pituitary gland shoots human growth hormone (HGH) into the bloodstream in rhythmic pulses during the deepest stages of sleep, between about midnight and 4:00 am, which is when kids wake up with complaints of sharp intermittent cramps in their legs and occasionally arms, groin, back and shoulders. I learned that it takes the body between twenty minutes to half an hour to metabolize human growth hormone, the same amount of time that a “growing pains” episode lasts.

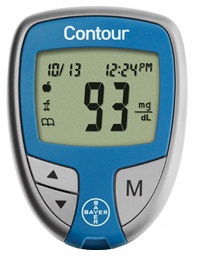

That’s when I began studying this twenty minute time period even closer. I wanted to find out what our bodies are doing while they’re using and absorbing human growth hormone, and if anything about this process might register with our senses — making some of us go, “Ouch!” The oft-repeated line by paediatricians that growing was “a silent and imperceptible process” felt wrong, quite frankly. Body wisdom told me otherwise. I abandoned the idea that growing pains stemmed from realtime stretching muscles and overtaxed tendons — too cartoonish, too Incredible Hulk. My research seemed to point to another, less obvious, culprit. When a diabetic friend of mine told me one day that her legs ached when her blood sugar was high — “like when I had growing pains” — DING, DING, DING, I wondered if high blood sugar levels might be to blame for my nighttime pulsating ache?

My focus turned to the side effects of high blood sugar. I learned that when HGH is released into the bloodstream it temporarily raises blood sugar levels, first by instructing the liver to make more sugar, then by convincing the muscles to get their energy from free fatty acids instead of sugar. With nothing to do and nowhere to go this rejected sugar makes it was back into the bloodstream at which point the pancreas senses an imbalance and tries to correct the high sugar levels by throwing insulin at the problem. But the muscle tissues couldn’t care less; for this short period of time — twenty minutes or so — while they are feasting on free fatty acids, they stubbornly ignore the incoming insulin which only makes the pancreas release more of the stuff. Again, I wanted to know how the body reacts to this struggle, producing an uncomfortable side effect? Does high blood sugar feel the same in all of us, whether we’re diabetic or not? I even started wondering is growing pains was like a case of temporary diabetes?

With the help of my Complete Home Medical Encyclopedia I ran my finger down the list of possible symptoms for hyperglycaemia (high blood sugar), past extreme thirst, frequent urination, weight loss and impaired vision until I landed on “leg cramps.” Bingo! Then I got my diabetic friends involved in a completely unscientific survey (I surveyed three people). “Have you ever had leg cramps?” I asked without telling them why I wanted to know. “When do you get them and how feel?” I learned from my friends that achy legs is one of their first symptoms when their blood sugar begins to climb. One subject, a friend at work who had Type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes, began reporting to me every time she had achy legs. “Test your levels! What are you at?” I asked. She consistently read between 10 and 12 mmol/L on her hand-held glucometer. Normal blood sugar readings are between 3 and 6 mmol/L. Being a doctor, I had no idea if her accompanying leg aches were related to her high blood sugar levels or poor circulation, another side effect of diabetes. This friend was new to diabetes — having been diagnosed three years earlier — but she hadn’t been told yet by her doctor that her circulation was suffering, so I stuck to the high blood sugar diagnosis.

I learned from my friends that achy legs is one of their first symptoms when their blood sugar begins to climb. One subject, a friend at work who had Type 1 insulin-dependent diabetes, began reporting to me every time she had achy legs. “Test your levels! What are you at?” I asked. She consistently read between 10 and 12 mmol/L on her hand-held glucometer. Normal blood sugar readings are between 3 and 6 mmol/L. Being a doctor, I had no idea if her accompanying leg aches were related to her high blood sugar levels or poor circulation, another side effect of diabetes. This friend was new to diabetes — having been diagnosed three years earlier — but she hadn’t been told yet by her doctor that her circulation was suffering, so I stuck to the high blood sugar diagnosis.

Now I was thinking, I need more proof. All I had to do is convince doctors to equip parents with glucometers. That way, when their non-diabetic children woke up in the middle of the night because their legs hurt they could take on on-the-spot blood sugar reading. If enough kids consistently registered above normal blood sugar readings (i.e. above 6), I may have just solved the mystery of growing pains.

But parents aren’t just curious to know what causes the pain, they want to know how to relieve it, or, better yet, prevent it. In 1988 Drs. Maureen Baxter and Corinne Dulberg, in co-operation with the University of Ottawa and the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, published what is now a frequently cited study in the Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. It claimed that kids with “growing pains” who performed regular muscle stretches at bedtime “showed more rapid resolution of their symptoms over an 18 month period” than kids who did nothing. But the doctors had no explanation as to why, at least at the time. That finding brought me full circle: maybe, I thought, that’s because exercise is one of the most effective ways of lowering high blood sugar. Just ask a diabetic. Apart from dietary changes, exercise is one of the first things their doctors tell them to add to their routine.

Afterword: I sat on my findings for over a decade, became a journalist, travelled the world, moved from one apartment to the next, then dusted off the banker’s box labelled “growing pains” a few weeks ago during a visit to my storage locker. When I went back to Google, now an infinitely bigger search engine than it was in 2000, I discovered that my hunch and my “leg work” were spot on. Since that time, growing pains has been taken up by researchers some of whom, like me, pinpointed complications from high blood sugar as a probable cause. Others, still aren’t sure. I was slightly ticked I didn’t beat them to the punch, but also amazed what focused research and a personal stake in the outcome can lead to. This was no Lorenzo’s Oil, but a fascinating journey for me nonetheless.

Spotlight: Vanishing accents

April 15, 2012

I’ve been covering music, and especially music and the internet, a fair bit lately. Here’s a piece I published last year that tackles the mystery of singing and accents. Enjoy!

SPOTLIGHT is Society Pages’ newest column focusing on questionable occurrences

In 1981, Sheena Easton was a 22-year old club kid with a glossy pout and a Lady Di shag when she burst onto the American music scene with a finger-snapping tune called “Morning Train.” The song went all the way to Number One on Billboard Magazine‘s adult contemporary chart. But when Easton sat down for her first interview with Entertainment Tonight, the production control room had to post subtitles across her bare shoulders to translate the singer’s accent — a Glaswegian cant so thick it strained Mary Hart’s smile and made TV viewers adjust the antennae on their sets.

In 1981, Sheena Easton was a 22-year old club kid with a glossy pout and a Lady Di shag when she burst onto the American music scene with a finger-snapping tune called “Morning Train.” The song went all the way to Number One on Billboard Magazine‘s adult contemporary chart. But when Easton sat down for her first interview with Entertainment Tonight, the production control room had to post subtitles across her bare shoulders to translate the singer’s accent — a Glaswegian cant so thick it strained Mary Hart’s smile and made TV viewers adjust the antennae on their sets.

The disconnect between Easton’s clear and powerful singing voice and her conversational brogue may have come as a surprise to the viewing public, but it makes perfect sense to voice experts who cite Easton, Liverpool’s Fab Four (that’s right, The Beatles), Sweden’s Ace of Base and Céline Dion, the chanteuse of Charlemagne, Québec, as good examples of strong regional accents that have been neutralized (or Americanized) by song. Diction lessons, mimicry and whip-snapping managers with US dollar signs in their eyes only partially explain this vocal transformation. That’s when I started digging for an answer.

“I’ve heard Chinese school kids with minimal English language skills sing songs in English with almost perfect American accents,” Randy Wong, a Boston-based professional musician and educator, told me in an email when I recounted the Easton story. And that’s because when children sing they rarely act self conscious about forming this mouths into big O’s, says Dr. Brian Hands, weighing in on this mystery. Hands is a Toronto-based laryngologist and voice care specialist who tends to the voices of COC opera singers, Stratford actors and visiting rocks stars. “You can mask any accent with a large articulator and resonator,” he says.

My reinterpretation of a greeting card, since lost.

My reinterpretation of a greeting card, since lost.

Here’s what he means: go on YouTube and watch your favourite singer — pop or classical — and you’ll find, says Hands, that “the best ones open their mouths like they’re going to swallow the stage.” They inhale using their diaphragm and when they exhale into song they promptly drop their tongue, their jaw (the articulator) and their voice box (the resonator), creating as wide a chamber as possible. “Such a large space means they can lengthen the time they hold their vowels, and it’s the vowels that are responsible for carrying the melody and the sound.”

Take Céline Dion. In person, she’s a fast talker with a pronounced nasality (Quebecois vowels are closed and nasal, wah, wah, wah).

Here’s a sample if you need a refresher (“Céline” appears at the 2:30 mark of this spoof about Canadian accents and -isms:

When Céline belts out one of her anthems — oh, like, “My Heart Will Go On” — she changes the shape of her vocal tract and stops letting air escape through her nose. “All that extra space and breath goes into managing an open-toned singing voice,” says Lorna MacDonald, a fiery soprano who is a colleague and patient of Doc Hands. “The expanded vowel space in her mouth leads to changes in pronunciation and a greater warmth and back-roundedness more typical of English speech patterns,” she explains. In other words, that process of stretching, rounding out and amplifying the vowels is what anglicizes most regional accents.

When she’s not on stage or in the studio making recordings for the CBC, MacDonald heads up the voice pedagogy program in the music department at The University of Toronto. I met with her at her office which is packed with books, music scores and anatomical models of human heads and chest cavities with brightly-coloured voice boxes caught in the throats.

But there’s one more consideration: accents are also about timing. At least, that’s what Marla Roth, a Toronto speech pathologist told me. “The same thing happens with people who stutter. We’ve found that when they sing, they don’t stall and trip over their words as much.” Everything in normal speech is about timing; you have to hit the right points in your mouth at the right moment. “In singing,” says Roth, the timing and intonation are off from normal speech, and that can result in a new speech characteristic.”

That leaves us, then, with only one mystery to solve. Mick Jagger. How is it that the biggest mouth in rock and roll turned an East London accent into a stuttering southern drawl?

P.S. Steven Tyler, another big mouth, doesn’t work in this story. Despite being from Yonkers he has a standard American accent with a slight tinge of surfer dude, so not much to overcome.

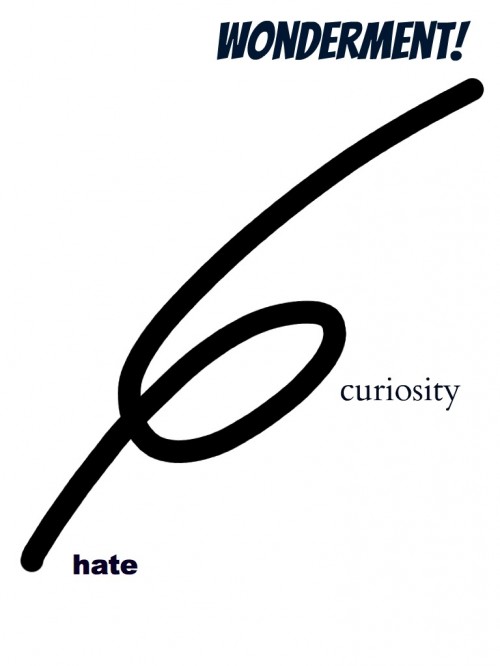

Idea loop

April 11, 2012

The circle of inspiration goes round and round and round.

My thanks to Neil Farber for sending and signing a copy of his latest book, Constructive Abandonment.

And in case you’re wondering how I inspired him …